I want to preface that this is not me trying to make some grand thesis statement on queer manga. To be honest, I’m tragically underqualified in that regard. I’ve read some Judith Butler, but I only recall it in parts. As far as the breadth of my queer manga reading, I don’t see myself as exemplary. I’ve read a handful of works, but I know that many other readers outclass me when it comes to this.

This post is more for me. As a pansexual guy, I’ve rarely explored gender and sexuality openly. It’s always felt private and cloistered. Perhaps I’m too hetero-passing, probably too heteronormative, but that was never home for me. I deeply value representation in media. I feel the viewpoints of the unspoken and unsung do more than just challenge the formats and media they belong to. It frees readers from conventions and norms, and normalizes what is often deemed the other. It’s in this private reading space that I can explore concepts that resonate with me, even when I feel like an outsider.

For full transparency, I will list out every manga I’ve read that can fall under the queer umbrella, barring a few exceptions that I will clarify (spoilers incomings):

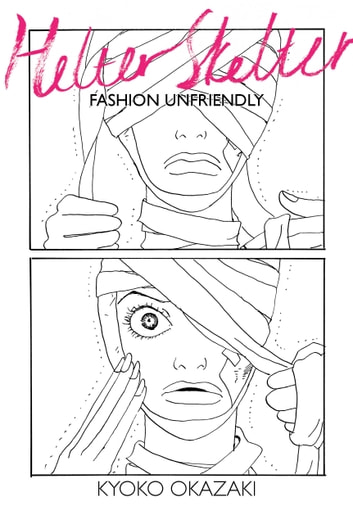

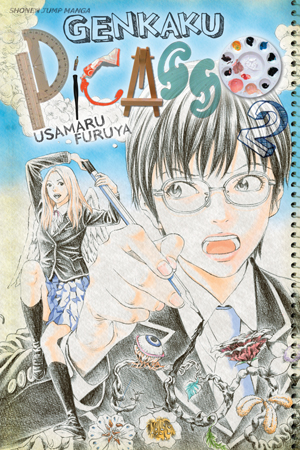

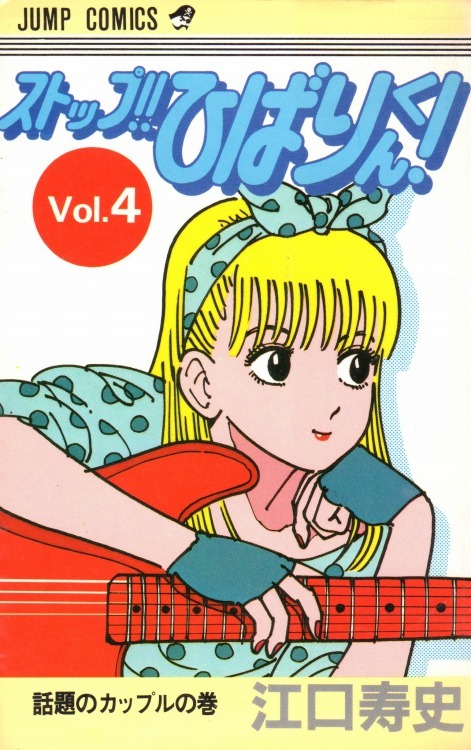

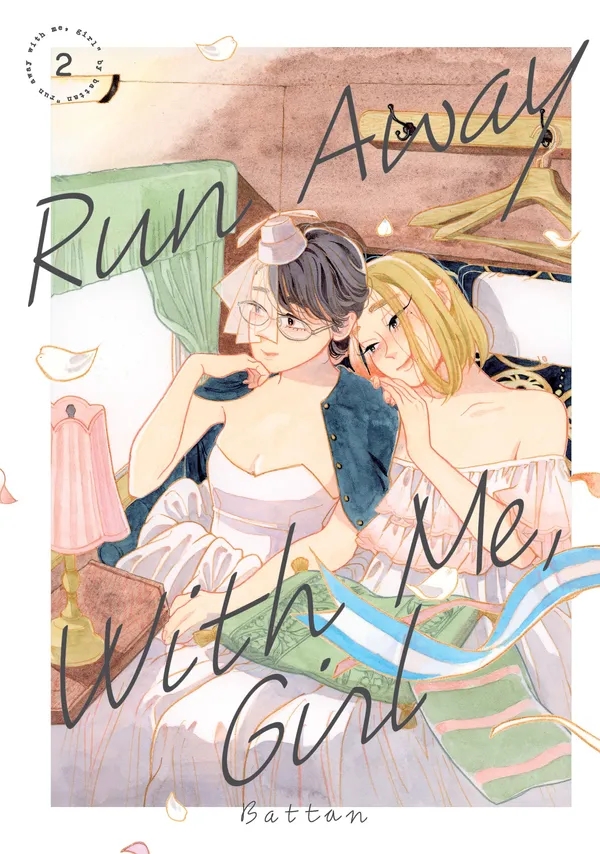

Sweet Blue Flower, Boys Run the Riot, Chocolate Strawberry Vanilla, Citrus, Fujouri na Atashitachi, Genkaku Picasso, Genshiken, Girl Friends, Helter Skelter, Wandering Son, Indigo Blue, J no Subete, Junketsu Drop, Run Away with Me, Girl, Kaori no Keishou, Lonely Wolf, Lonely Sheep, Marginal, MW, Not Simple, Oddman 11, Ohana Holoholo, Paradise Kiss, Pieta, My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Our Dreams at Dusk, Stop! Hibari-kun!!, The Heart of Thomas, Tokimeki Mononoke Jogakkou, and Unmei no Tsugai ga Omae da Nante.

I excluded YuriCam because the story doesn’t treat the queer element as anything other than a joke, Bra Girl and Boku Girl because I’m not entirely sure how to assess gender bend stories, and Boku no Futatsu no Tsubasa because it is just flat-out awful. I’m also excluding implicit or headcanon assumptions of queerness such as Kids on the Slope and Berserk.

The extent of queerness across these works can vary. There are instances where they are stated, but not the focus; instances where they receive momentary focus in an arc; instances where they are the core subject. Regardless of their prominence, I think about them. There may be other instances of queer representation that I’ve forgotten, but this is what I can say for sure.

Manga like Not Simple are strange to include in this post since the story revolves around Ian, who does not have any queer elements that speak to his identity. However, a good chunk of the story is seen through Jim’s perspective. His inclusion does a lot for the narrative, even if he isn’t the focal point. His position as a gay novelist estranged from his family makes him both empathetic and curious about Ian’s plight. The friendship they share is the most comforting thing in this manga, even if Jim’s identity as a gay man does not factor in too hard.

As touching as that may be, it doesn’t resonate with me. I don’t learn anything about my own queerness while reading it. Not a shot at the manga (it’s literally one of my top 10 favorite works,) but it doesn’t help me on this front, and neither do manga like Tokimeki Mononoke Jogakkou, Unmei no Tsugai ga Omae da Nante, Chocolate Strawberry Vanilla, Kaori no Keishou, Oddman 11, and Junketsu Drop. Most of these works revolve around the eroticism of BL/GL, as well as specific sub-genres like omegaverse relationships. It feels more like engaging with genre than with the humanity of the queer experience and its difficulties. Although I will admit that Tokimeki Mononoke Jogakkou and Junketsu Drop have cute high school romances and Oddman 11 is delightfully funny.

There are also mixed bags in this bunch that I have a hard time trying to parse in terms of their queerness. Citrus isn’t just an incest story, but it’s a toxic one. The relationship between Yuzu and Mei is twisted and manipulative. I can’t really think of anything redeeming or interesting about them. Helter Skelter has an even more malicious relationship between Liliko, Hada, and her boyfriend. It’s interesting because of how selfish and cruel Liliko is, and the relationship is never painted positively or romantically, but it doesn’t give me insight from an emotional perspective. MW presents the a serial murderer as a gay man, and throws a priest into a crisis of faith because of his attraction to the killer. Not necessarily something I’d draw from.

Genshiken also rubs me the wrong way as the one instance where transphobia is championed. Note that this is just my interpretation and I’m not trans, but Hato is repeatedly ridiculed for being trans. Even when the manga finally makes the turn towards tolerance, it is towards Hato being a MTF crossdresser, rather than being authentically female. I feel as if there was narrative gaslighting to muddy the once-solid position of Hato clearly identifying as a woman. This never sat right with me, but that is just my perspective on the matter.

There are instances of trans representation that I like. The most controversial one might be Paradise Kiss; not because the representation is poor, but because the manga itself has a lot of problematic parts. On her own, Isabella is lovely and her bond with George is great. There’s legitimate acceptance of each other and a friendship that runs deeper than love. It’s also comforting that her self-identification does not waver. The issue is Arashi. Everything about him is gross. He is scum and the manga would be better off if he were completely jettisoned.

In Stop! Hibari-kun!!, there is discomfort when it comes to how everyone treats Hibari. Everyone is incredibly transphobic, which does match the time and culture, but Hibari is unphased. At no point does Hibari question or retract who she is. She is a girl. A girl with very questionable taste in men, but a girl nonetheless. She is the shining beacon in a manga full of questionable content. I appreciate that internal fortitude and commend mangaka Hisashi Eguchi for that one thing.

In contrast, Boys Run the Riot and Genkaku Picasso deal with accepting one’s true gender. Both are set in high school and show that identity can’t just be internal, but it requires social acceptance. Ryou and Jeanne know that their assigned genders make them deeply uncomfortable. They express their true selves away from people who would recognize them. They are both alienated for their truths, but are welcomed by those who confront their own social prejudices and biases. It’s not enough to know who you are. Sometimes, it’s important that the others around you know you as well.

One of the hardest reads has got to be J no Subete. The story of a transwoman growing up in the Rust Belt during the 50s-60s was always going to be difficult, but damn did this manga push it. There are some moments here that are so graphic, that I’d caution many people from reading it. But J’s story, her plight and her determination to be authentic to herself, is so powerful. It isn’t clean, it isn’t without issues, but it is painfully human.

The last batch of queer manga depict sexuality in ways that are engaging for me. Lonely Wolf, Lonely Sheep is a simple love story about sapphic women who learn more about each other and choose to be together despite their baggage. It’s a really short and quaint story if you remove the possessive psycho chick who tries to injure one of the girls. Sweet Blue Flower is a poignant romance between high school girls who struggle with valuing friendships over personal happiness. It is hard to come out to the best friend you love. It’s a sweet and heartbreaking story that has one of my favorite lines in romance manga, “Maybe I fall in love too easily. But that’s the only way I’ve ever loved women.” Seriously, just gut me and leave me bleeding, thank you.

Fujouri na Atashitachi shows the lives of adult sapphic women, situating their romances within their office and social lives. It’s far more effective when reaching older readers, especially wlw readers. Another sapphic manga oriented at older readers is Run Away with Me, Girl. Two former high school girlfriends, reunited after years of distance, finding solace in each other once again. A romance full of forgiveness, healing, and affection.

There were two more adult-oriented lesbian manga that I’ve read. Indigo Blue shows a messy relationship full of indecision and deceit, while also being grounded and subtle. The manga either ignores or dismisses bisexuality, but it still has good moments. Nothing can compare to My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness though. That manga is a revolution. Probably the singular best confessional nonfiction manga to have ever been written. It’s bare, it’s honest, it’s vulnerable, and it’s painfully relatable. The way Kabi Nagata relays her yearning for some physical touch and affection is emotionally devastating.

As for the remaining lesbian manga centered around high schoolers, the two I’ve read are polar opposites. Pieta is a romance between two girls in difficult situations, especially Rio. It deals with heavy topics like abuse and trauma, but finds comfort in the bond made between two girls. To contrast, Girl Friends is about the fears and joys that come with realizing one’s sexuality. It also has a lot of shopping and hanging out that give the manga a youthful feel. It’s as serious as it needs to be without compromising its cuteness and levity.

Neon Genesis Evangelion’s manga still has gay elements, but they’re handled differently than in the anime. Kowaru is introduced sooner and has a more mercurial relationship with Shinji. In a sense, the gay angle feels like it shifts more toward Kowaru than it was originally. Shinji isn’t as ambiguous as he was in the anime. Regardless, their story is still a crucial moment in the manga, even if it’s more one-sided for Kowaru.

On the topic of tragic gay romances, The Heart of Thomas feels like the prototypical doomed gay story. Where being gay sentences characters to a life of misery and emotional complication. It is very effective as a melodrama, but gay romances deserve to be more than just being tortured stories.

The last batch of queer manga that I’ve read deal with a large breadth of the lgbtqia+ spectrum. Ohana Holoholo has bisexual women, Marginal has an intersex lead, Wandering Son is all about gender expression, and Our Dreams at Dusk covers so much.

I appreciate the complex relationship between the two bisexual women in Ohana Holoholo. I love how it handles feelings of abandonment and distrust. It’s understanding and empathetic. I just wish Nico’s story as a bisexual man was handled far better. In Marginal, the concepts of gender and sexuality are played with and experimented on to strange degrees. It really feels like an epic sci-fi story that uses gender in its fiction; less of a reality and more of an idea. There’s something otherworldly about how Kira is presented as an intersex person. The presentation feels a bit othering, but maybe I need to cut it some slack. As far as I could tell, it wasn’t malicious.

I have so many mixed opinions on Wandering Son. I made my peace with it when I accepted that it isn’t a story about trans people, and shouldn’t be marketed as such. It is about fluidity and growth, seen through the eyes of kids. The manga doesn’t reject trans identities as it presents Yuki as an adult woman who lives out her life as a woman, but it explores gender in a way that may be upsetting for those in the throes of gender dysphoria. Ultimately, it still rejects gender conformity, which I appreciate, but it can’t be called a story about the trans experience.

Finally, Our Dreams at Dusk is a story about community. In a largely cruel and bigoted world, it is important to have a community who understands you and gives you the space you need to be authentic and real. The manga has a gay character, lesbian characters, a transmasc character, an asexual character, and a kid who is still trying to understand their own identity. All are there for each other. It is beautifully expressive, and thoroughly affecting.

This is, without a doubt, my most aimless blog entry to date. If you’ve managed to read this far, thank you. It is also my most naked and honest entry. I’ve been trying to be more honest with my queerness. In the process of writing this, I’ve opened up to my own mother. Something that I’ve been wanting to do for years. I read these manga because I want acceptance for who I am. I feel that is why many of them are written, especially when they’re made by queer people. I will continue to read works like these, and make a home for them within me.