If you’ve read my blogs before, you’ll know that I often won’t read manga that are ongoing. This saves me the pain of having to wait and the uncertainty of a work’s fate, but it comes at the cost of not really knowing the new works out there. That issue is the most glaring when it comes to my ranking the 2010s. There are a lot of promising works from that decade that aren’t complete yet. This greatly limits the manga that I read from that decade. Additionally, I want to emphasize that my considerations require that a manga’s publishing date starts within the 2010s for it to qualify. So stuff like March Comes in Like a Lion (which is still ongoing) doesn’t count.

There a lot of promising works from this period that are on my radar, but I can’t actually say if they’re good nor how good they are. Some examples of this are Witch Hat Atelier, Go With the Clouds, North by Northwest, Kowloon Generic Romance, and Yume no Shizuku, Kin no Torikago.

I’m dying to read all of those, but my own restrictions keep me at bay. Fortunately, there were works that were previously on my radar that have ended (or are slated to end soon.) So, I’ve been able to get a taste of what the decade can offer and am thrilled at how good it’s been so far. Time will tell if this decade can live up to the 2000s, but my current top 5 spells some promise.

At Number 5:

Delicious in Dungeon overflows with a fanatical love for Dungeons and Dragons and other fantasy role playing games. The world building is staged as if it’s one big campaign. There are many charming elements in the manga such as the cooking, its humor, and Kui’s ability to create distinctly varied character designs. If that’s all this manga was, then I would still think it’d be an enjoyable read.

However, the story takes a turn somewhere after the Red Dragon arc that complicates the journey and allows Kui to really deepen the world building. The deeper it goes, the more readers start to see how it’s tied to the narrative. The world becomes far more alive and textured, setting itself apart from other fantasy settings. The concept of a dungeon becomes an active element in the story rather than being a static setting which people are familiar with. It’s through this that the story is able to ask some of its themes. Why do people seek adventure? What do they wish to gain? Is it worth it in the end?

What I didn’t expect were the turns it would take with both Marcille and Laios. There characters were fleshed out and developed in ways that genuinely excited me. The manga zeroed in on their obsessions and almost made me scared of them. The ways our wishes can warp us was put on full display with these lead characters. The deeper they went, the closer they got to unraveling the mysteries of the dungeon, the more their obsessions consumed them. This was the aspect that made me really love the manga.

At Number 4:

Golden Kamuy delivers what I would consider the best ensemble cast of the last 20 years. Over 40 characters, all with their own machinations and priorities, forming uneasy alliances in order to get buried gold. Each character is memorable or develops incredibly. Asripa is probably one of the best female leads I’ve read in a manga, Tsurumi is one of the best antagonists I’ve read in a manga, Ogata is one of the best minor antagonists I’ve read in a manga. The cast is so stacked, it’s ridiculous. You will have a favorite, guaranteed.

This isn’t even mentioning how arresting the setting is. Japan during the Meiji era, after the Russo-Japanese War, is a setting that is rife with militarism and expansionist aggression. To set the story there, but to center on neutral parties like the indigenous Ainu people, allows for the setting to really highlight the internal tension within Japan. It shows the Japanese military as this voracious force that is seeking to rival all of its neighbors. There are many groups who have their own goals and intentions, including the Ainu people, but they have to clash against warmongering military units.

It’s astounding that this manga can still contain moments of levity and humor, while the story is incredibly grim and tense. Don’t get me wrong, Golden Kamuy is a goofy manga, but it contains a ferocity and sharpness to it that is rare within the medium. It is a twisty story full of characters you cannot trust set to a backdrop of warfare and drama. If that’s not engaging, I don’t know what is.

At Number 3:

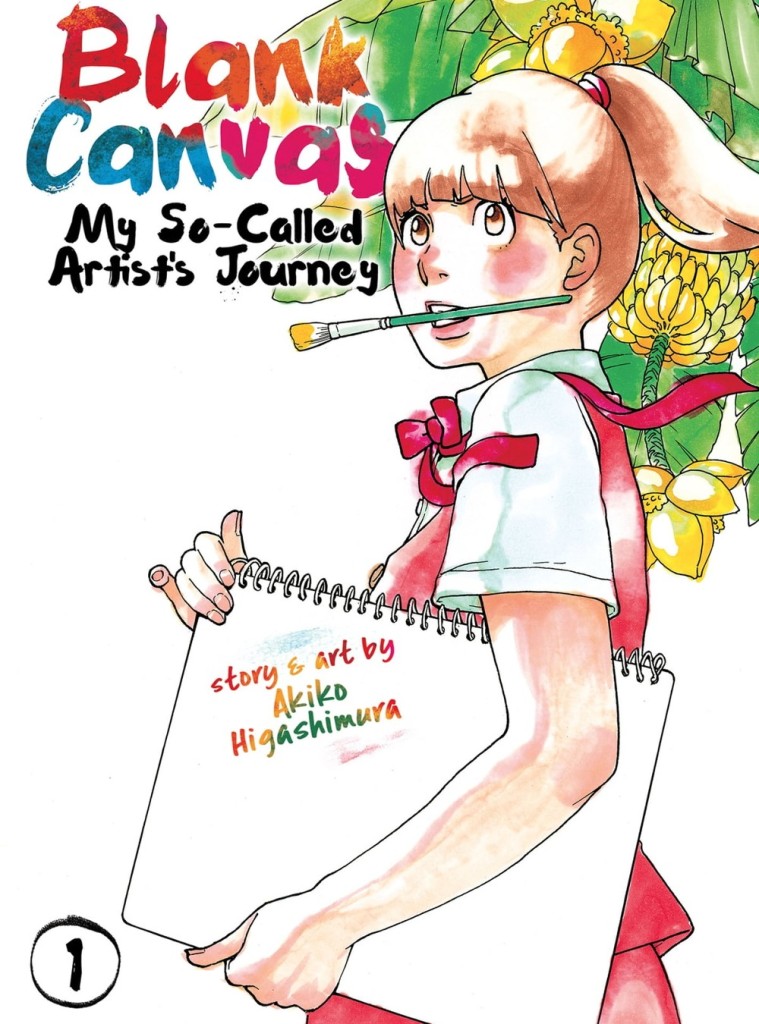

Blank Canvas: My So-Called Artist’s Journey devastates me every time I read it. This is one of the best depictions of grief and regret that I’ve seen in the medium. A self-biographical work by Akiko Higashimura, it is less about her journey and rise as a mangaka, and more a mediation on her self-hatred and failures as an artist. Without getting too personal, I relate to her at her worst, so this manga absolutely eviscerates me whenever I read it.

The manga foreshadows its emotional undercurrent through biting remarks at the end of Higashimura’s recollections. She’ll end a volume thinking about her time at the art studio or at college, but follow it up with comments that almost fester with contempt. There is so much pain when it comes to her relationship with art. Her frivolous nature is at odds with the expectations given to her by her teacher. She feels like a coward for following the path she did, even if it gave her the results she wanted.

This is an incredibly raw retelling of one’s artistic growth. Its insightful, but not sterile. It’s emotional, but not unfocused. This is Higashimura recounting her life with enough distance to see things clearly while also being as vulnerable as possible. That is the ideal of a nonfiction work. Higashimura knocks it out of the park with this. Cathartic, heartbreaking, funny, and consoling. No best-of-the-decade list should be missing this.

At Number 2:

Sunny presents a window to look at children dealing with abandonment. The titular Sunny is an old junked car by the kids’ orphanage. It gives them an outlet to imagine far flung lands where they can escape the reality of being orphans. This is undoubtedly Matsumoto’s most grounded work. A lot of his fantastical or surrealist leanings give way to an earnest portrait of children burdened with the thought that they don’t belong and that they aren’t loved.

This is not a fun read. When I first checked it out, I was thoroughly crushed by the emotional weight. Matsumoto does a phenomenal job at painting their mundane lives, their quirks, their flaws, their cruelty, and their humanity. He does excels at convincing the reader than these are kids. Without a sense of family, the kids form bonds and connections within the orphanage. Those moments ground the story and prevent it from becoming an overwrought melodrama.

For the longest time, this was the manga that I thought was the best of the decade. Honestly, I have a hard time really expressing the effectiveness of the story. It cuts right through you without being manipulative. The best I can do is compare this manga to a Kore-Eda film. In fact, if Kore-Eda would ever adapt this manga, it’d be a perfect match. It’s potent and real. So much about it rings of the ennui that lives within kids, much more the ones who’ve actually been abandoned. This is Matsumoto’s best work and that’s saying a lot.

Honorable Mentions:

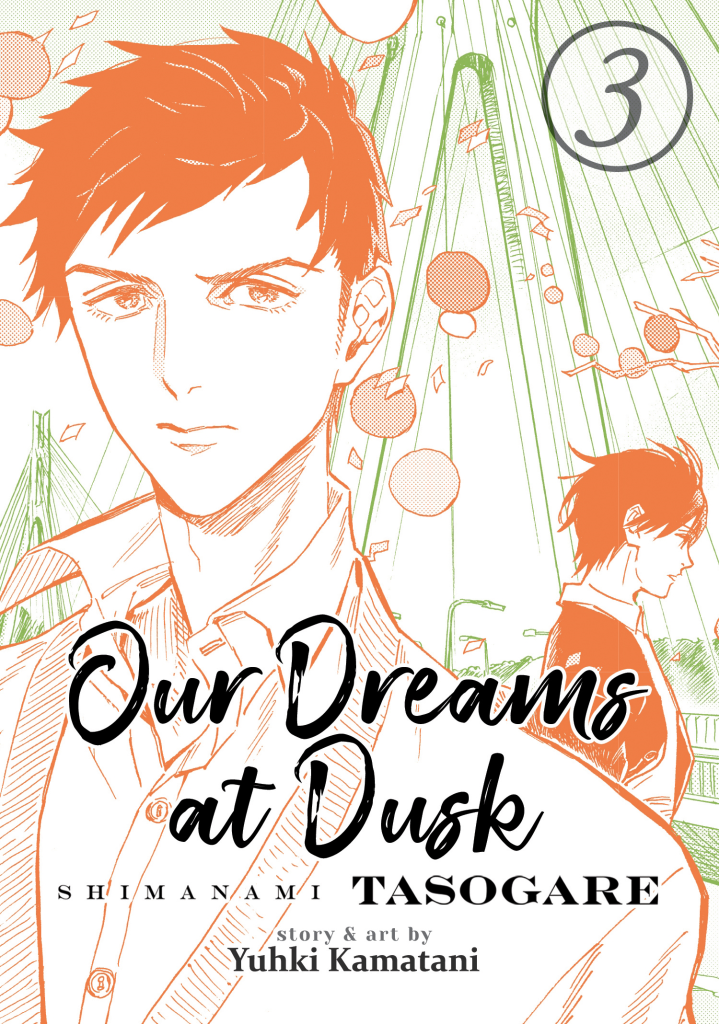

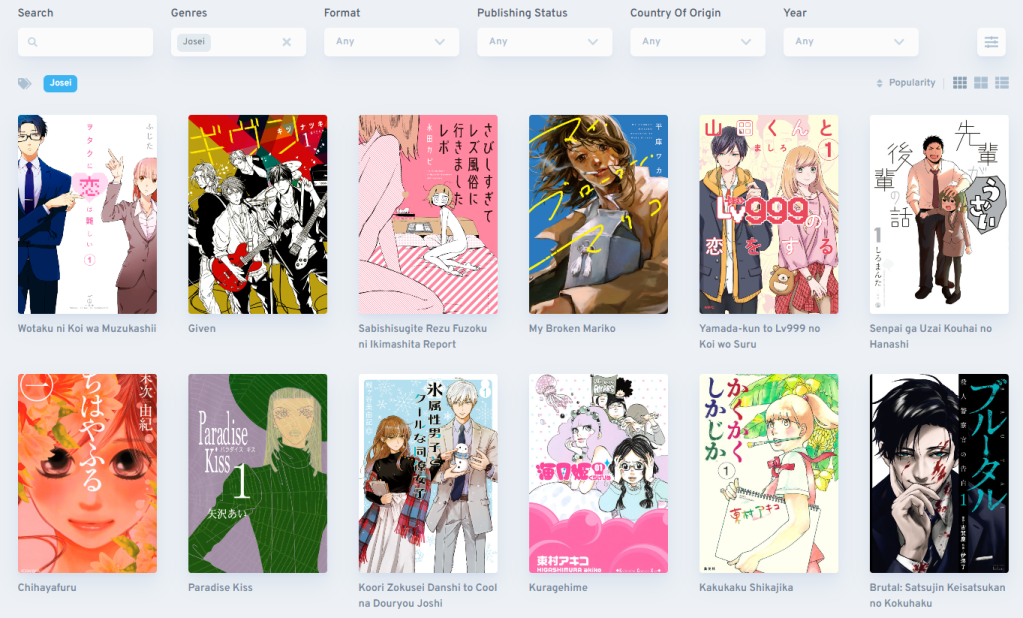

There are many manga that I would love to give honorable mentions to like Run Away with Me, Girl, Sweat and Soap, Rojica to Rakkasei, The Girl From the Other Side: Siúil, a Rún, Mob Psycho 100, Kaguya-sama: Love Is War, and Spirit Circle, but the three I want to really zero in on are Our Dreams at Dusk, Girl’s Last Tour, and My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness.

Our Dreams at Dusk is a dazzling and expressive look at gender, sexuality, and expression. I wish it had more room to explore certain characters, dynamics, and facets of the LGBTQIA+ community. For what it’s worth, what it does manage to accomplish in its limited run is very good. Girl’s Last Tour blends apocalyptic dystopian settings with a soft tone and aesthetic. There is very little immediate danger left in the world. Just two friends marching through the wastelands of society, trying to make the most of their time together. The end result is this somber, but often comforting story that really hooked me in. My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness overflows with an anxiety and depression so real that it cannot be denied. This confessional manga by Nagata Kabi highlights the isolation that ordinary people in Japan can face, especially queer folk. The retelling is so raw and honest that it might shake people who are experiencing something similar. Regardless, it’s a manga that must be read.

At Number 1:

Land of the Lustrous is a relentless force that will never take it easy on the characters or the readers. What appears to be a quaint story of sentient gemstones quickly unravels into a maddened story about identity, isolation, existential dread, and oblivion. Its main character, Phos, is the unfortunate subject of one of the cruelest character arcs I’ve read in awhile. I have not felt this bad for a character since Goodnight Punpun.

The story is twisted, but captivating. The mysteries of the story only lead to further heartbreak. Learning about the Lunarians, about Kongou, about the origins of the Lustrous, all of it only shatters Phos further. And yet, the progression is nowhere near indulgent in its cruelty. This is not perversion for perversion’s sake. The journey is a methodical exploration of Buddhist teachings and the mercurial nature of humanity. The manga is able to communicate those with no pretense nor condescension. It delivers the themes through character drama. Every second of it can capture the reader.

I broke my rule for this manga. As of writing this, the manga has not concluded yet. However, it’s final chapter will be released in a few weeks so I read it regardless. This manga deserves all of the praise it gets. From the fantastic journey that Phos goes through, to Ichikawa’s undeniable compositions, to the unflinching delivery of its final chapters, Land of the Lustrous deserves all of the praise.

The Rest of It…

I can’t say which manga will eventually round out my top 10. There’s no guarantee any of my honorable mentions make it once I’m confident enough to put out a top 10. However, the 5 works that are currently in that list serve as proof that whatever else comes my way, I’m sure it’ll be amazing. I’m not sure if it can live up to the 2000s, but no other decade has. It will still be an amazing one to get through. Hopefully, some of the promising ongoing works end well so I can include them, but only time will tell. (Witch Hat Atelier, you better make this fucking list I swear!)

Thank you so much for reading this list. I hope I’ve encouraged any of you to check out any of these manga. Let’s enjoy manga together!