It is difficult to decide which approach to nonfiction in manga is better: Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s distanced recollection of time or Akiko Higashimura’s sentimental introspection. As lauded and talented as both of the mangaka are, their greatest works happen to be autobiographical retellings of their artistic journeys. Tatsumi gives a detailed look at his upbringing, full of historical landmarks and informed by the context of its time. Higashimura paints an impassioned reflection of her life, her regrets, and her quirks.

As someone who writes personal essays, the process can be harrowing. It requires inward examination; often pushing the writer to some degree of discomfort. The point of nonfiction goes beyond just divulging personal events as they are. It is a distanced reflection that allows the mangaka to glean more meaning out of their days.

However, there is room for confessional works such as Kabi Nagata’s My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness, but that approach will not work most of the time. The challenge with confessional nonfiction comes when the reader asks why. Why am I reading this piece? Why is the mangaka airing out so much of their personal life? Why does any of it matter?

Kabi Nagata’s works are extremely special in that regard. The ‘why’ is silenced by the overwhelming power of the manga’s expression. It is a work that begs to be read, to be empathized with, to be understood, and to be cherished. Nagata is not incredibly introspective and self-critical, but she brings out the painful and relatable humanity of her life.

While the confessional approach can work, it can also lead to the mangaka vomiting out unprocessed memories that weigh the reader down. That is why the two works that I think represent the genre the best are A Drifting Life and Kakukaku Shikajika. Both are incredible manga, but they achieve success through different approaches.

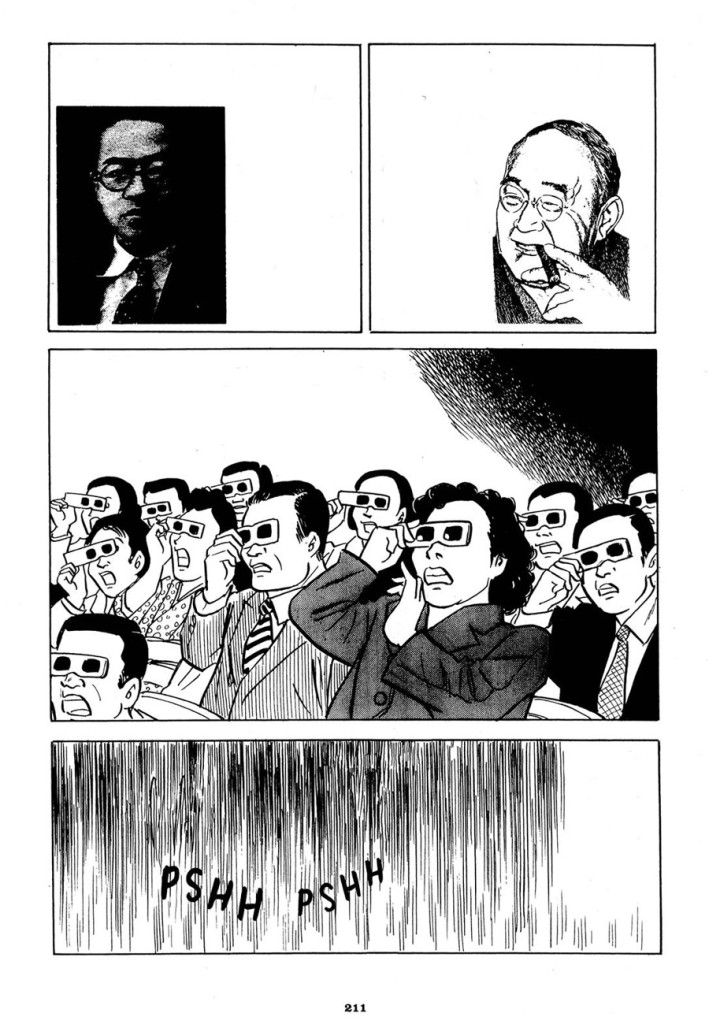

In A Drifting Life, Tatsumi ties his artistic journey with the time and culture he grew up in. He will show a younger version of himself working on a manuscript, then follows it up by mentioning events in politics and the first screening of a 3D film in Japan. While these moments may seem disconnected from Tatsumi’s struggles and aspirations as an artist, they inform the landscape of the text. It is through details like these that viewers understand what influenced Tatsumi. It paints a very clear picture of the environment he was in.

With a detailed portrait of the time to work with, Tatsumi is able to communicate his feelings about manga, entertainment, and genre. It shows the evolution of the medium through his eyes; a glimpse at an important point of manga’s history through one of its legends. A Drifting Life is just as much a story of the history of manga and post-World War II Japan as it is about the life of the late great Yoshihiro Tatsumi.

That is not to say the manga is not a personally involved work. Tatsumi makes sure that the story carries his emotions and struggles. When his brother rips a letter by Noburo Ooshiro, you can feel the pain he feels as he curls up and collapses in frustration and sadness. The posture and body language of his younger self communicates the anger and determination despite the simplistic character designs.

In contrast, Kakukaku Shikajika is unrelenting sentimentality with introspection serving as its backbone. Akiko Higashimura is able to communicate the raw intensity of her emotions as a younger woman, but injects poignant and melancholic notes when reminiscing them as an adult. She is not divorced from her childhood naivety and temperament, but understands the pain her actions caused others. This makes the manga a rollercoaster of feelings. She could be joking about her celebrity crushes in one page then lamenting over her art teacher by the end of the chapter.

Outside of Kakukaku Shikajika, Higashimura’s core strength is her humor. She has some of the most immediate and satisfying jokes and gags in contemporary manga. This strength is visible in her autobiographic work, but it is no longer the draw of the story. Her earnest and vulnerable thoughts bleed across all of the panels, and that is what makes the manga so captivating. Her pain and regret is sharp and clear, hovering over all of the times she failed her art teacher.

During the final volume of the manga, Akiko Higashimura talks about the process of creating Kakukaku Shikajika. She explains that she does not think about the process too heavily, even adding that she can start and finish a storyboard hours before the deadline. However, the manga forces her to confront the memories she has tried her hardest to forget. Memories of abandoning her teacher when he needed her the most. That frustration and self-loathing guides the manga’s contemplations. As a veteran mangaka, she now understands that she did not have to abandon her teacher, but she still did.

In a way, comparing these manga’s approaches can be pointless. Both are award-winning works that speak on artistry and showcase different time periods. Each work is extremely valuable. These are not points I would contest. However, there are aspects in each manga’s approach that writers and mangaka might want to consider when viewing the text.

A Drifting Life is made by a legendary mangaka whose insight is only possible due to all of the knowledge he accrued in the business. To be able to use history as a foundational part of a nonfiction piece requires deep expertise in the field, as well as decades of experience. In comparison, Kakukaku Shikajika is more personal. The reflections in the manga take years to process and accept, but it is achievable for most.

This will also apply to the readers when choosing the kind of nonfiction to read. There is a level of separation expected in works that take on a historical angle. This may lead to drier texts, but it is also full of insight and experience. The birth of the Gekiga movement is a fascinating topic to learn about as a manga reader, as it shows how creative minds rebel against conventions and take inspiration from other media. Akiko’s approach may come across as more intimate and personal, appealing to readers who like narratives with immediacy and gravity. However, the strength of her emotions might deter readers who do not want to be overpowered by sentimentality.

There can be other ways to approach nonfiction in manga. Kabi Nagata is an example of how versatile and underused this mode of narrative is for the medium. Standards are meant to be pushed, and the canon will give way to new innovation. As an essayist, this excites me. Providing two examples of extremely successful approaches does not solidify them as the only routes, but showcases their individual merits (also, I just wanted an excuse to reread them.) As writers, readers, and fans, we can appreciate autobiographical works more thanks to A Drifting Life and Kakukaku Shikajika.

Manga recommendations on the topic:

- Kakukaku Shikaji by Akiko Higashimura

- A Drifting Life by Yoshihiro Tatsumi

- My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness by Kabi Nagata